Writings

On Perspective

Letter to Peter Schjeldahl

Perspectiva, 2000 | oil on canvas, 80 x 96 in. | Private Collection: Los Angeles, CA

This is not a letter for the Mail section, but I must correct a very large misstatement made in the Art section of the March 9th issue. This was an off-hand remark in the brief review of the Giulio Paolini exhibition at Marian Goodman. In it the writer states that, “one-point perspective (is) the foundational lie of Western Art.”

It is true that every time we shift our position or turn our head we have a different perspective but each time the rules follow us and create a new truth. To stand on a railroad receding across a flat plane, one is seeing a perfect reflection of exactly where one is standing. To think otherwise is simply ignorant. It is one of the truest things on earth that no matter whether we are at sea level or on Mt. Everest, if you hold out a level at eye-level it would point exactly to the horizon. What changes is how far away that horizon is and how far you can see. Nevertheless everything corresponds to that fundamental truth.

Giotto eye-balled it pretty well but he didn't understand it the way that Brunelleschi or Piero did. They nailed it. What is even more impressive was the later discovery of measuring points to create a three-dimensional image from a floor plan and an elevation. This was a brilliant intellectual discovery and while it might to a degree be a fiction, it is not a lie any more than is a novel when it reveals an invented truth.

The teaching of perspective has been dropped from nearly all art curriculums even though it is as intellectually delicious as mathematics. Contemporary art’s methods have become as conventionalized as the French Academic art of the 19th Century was. It is now entirely formulaic even when it purports to be inventive. As one critic put it, it has become “predictably quirky.” Its predictability is what draws the enormous prices at auctions and at galleries. It is what all museums want now and what all the schools are teaching. Contemporary art in all its many forms is now literally Academic and very far from the bravery of the early Avant Garde Modernists.

Many years ago I asked myself, if Duchamp were alive today what kind of art would he be making? I believe that that he would be making history paintings because, like his “Fountain,” history paintings are wholly unwelcome within the context of contemporary art. Serious history paintings, not ones caged in formulaic irony or made “relevant” by agitated expressionism are the new challenge.

My own personal perspective is not one of conservatism. I despise the so-called Classic-Realists (sic). Theirs is a kind of formulaic mushiness of light, subjects and technique. Indeed, realism itself, the representation of present day life has become a near total cliché. The insistence that art must be a reflection of the life around us whether by way of Realism or Readymades has become narrow and narcissistic. It is a form of chronological chauvinism.

History painting as a new radicalism would merely be another form of gratuitous stylistic shifts if it wasn’t something that was hugely needed to redirect the culture. As I have said for many years, we are in need of a renewed desire for knowledge. Just as Modernism – particularly Surrealism - made us more aware of the irrational world inside and out, we must now be made desirous of the rational. Conservatism and fundamentalism now own the irrational. Liberal politics and aesthetics need to redirect their cultural energies away from a whole litany of easy cliches toward what the Chinese have called a “passion for learning.” Art education that teaches only how to emulate images seen in Artforum is like teaching math by arranging random numbers. There is a science to seeing just as there is to biology. Light, form, color, physiognomies of plants and animals and even perspective are all very teachable. Realism aside, they teach us how to look carefully at something, analyze it and then recreate it using our knowledge of all of the extant elements. The student is not looking for a mere “impression” of something but the fundamental truth to its existence.

And so, getting back to perspective, there is no “lie” but instead a whole system of agreement set up by the exact position of each individual viewer and all within their view. It puts the visual world into an order that is supremely liberal in that it believes in the rational interrelationship of all things. Art itself becomes a metaphor for carefully looking at, analyzing and then acting with full knowledge.

David Ligare, March 14, 2015

Realism and the New Ideal

A dialogue between Robert Dickenson and David Ligare

Et in Arcadia Ego, 1987 8 1/2 x 12 in. | Private Collection

Robert Dickenson: As a warm-up, what would you say

is the opposite of art?

David Ligare: Oh. I

would say that the opposite of art is ignorance. Beyond the technical aspects

of making art, there is a language that allows us to truly see a work. All art

exists within a structure of critical and historical knowledge

that is constantly evolving and being reevaluated - just like

language itself. For example, when I was teaching I would make a

drawing on the board and ask the class to identify it. It was very clear and

precise but no one ever guessed correctly that it was the Japanese

character for rain. My point was that art, all art from ancient to

contemporary, is a language and unless you understand the

vocabulary you can't really see it. Moreover, the language keeps shifting,

inventing and then reinventing itself. That said, I am probably wrong in

accepting as much of the contemporary art world as I do. Much of

it is way too clichéd at this point.

RD: Would you say that there are critics and

curators today who can't see your work or the work of other Realists?

DL: Absolutely, if you read Artforum or

visit the Whitney Biennial or the Basel Art Fair there are

almost no straight-away representational works. Despite the extreme diversity

of methods and styles, representation is barely represented,

it's just not in vogue right now, despite the fact that Realism

is the foundation for our own modernity.

RD:You've been making paintings based on history

for many years now, how do you see yourself, then, fitting in to the art of

our own time?

DL: I don't

fit in but, because I know the history of modern and contemporary art pretty

well - I used to teach it - I become part of it simply by way of my knowledge

and awareness of it. Does that make sense? I pay attention to it because it's

interesting and because it's good to know your competition. By competiotion I

mean competing philosophies rather than products. But I also think that

despite our differences, there are things to learn from contemporary art just

as there are things to learn from life. I also believe that the true purpose

of art is to fulfill societal needs and, while modern art had much to teach us

earlier on, like almost all art movements, it's become repetitive and

superficial and has basically been feeding off of itself. I believe that what

we need now is an art that is skillfully representational and that is not

fixed to the present but is historically fluid and flexible. The great early

Renaissance architect and artist, Filipo Brunelleschi looked back over a

thousand years at the art and architecture of ancient Rome and from those

ruins he helped to create a new modernity.

RD: Yes, but, we're modern in a different way

today. The Poet, T.S. Eliot once wrote that "it is exactly as wasteful for a

poet to do what has been done already as it is for a biologist to rediscover

Mendel's discoveries." As a realist don't you sometimes feel like this has

been done so often and for so long, why bother with it? Why bother to reinvent

the wheel?

DL: Well,

strictly speaking, I'm not a Realist, I'm a Classicist and the two are

mutually exclusive, but I take your point about originality. Eliot was a

great, maybe THE great, modernist poet but remember, he also wrote an essay on

tradition and its role in art. And, just as you say, we're modern in a

different way than we were in the late middle ages, the traditional is now

different too. What is often called "traditional" is often a form of (naïve or

uninformed) contemporary Realism. Eliot's form of tradition meant the full

knowledge and use of history. Eliot was an "eternalist", he begins his poem

The Four Quartets by saying, "Time present and time past/ are both perhaps

present in time future." More importantly for me, his poem, Burnt Norton,

especially the part beginning with "At the still point of the Turning world,"

exactly echoes the work of one of my greatest influences, the Greek Sculptor,

Polykleitos. Nearly everything that I've done for the past thirty years or

more has been aimed at finding the center or "the still point" within the

swirl of time and culture. Most contemporary artists are straining to be

"edgy." "Predictably quirky" is how one critic put it. That said, I do agree

that originality is important, if only for the sake of change and fashion, but

we have to ask ourselves, what IS originality? When there are thousands of

neo-expressionists, thousands of conceptual and installation artists,

thousands of eccentric-abstractionists and thousands of every category that

you might find in the most current graduate school programs and in the pages

of Artforum magazine. The so-called "edge" in the artworld is a very crowded

place.

No, the truth is that originality is no longer original, or as the

comedian, Lily Tomlin said, "What do you do when everyone's marching to a

different drummer." Compared to the so-called avant garde artists of today,

the early modernists were a brave breed apart, we have to admire them

tremendously. They were working in a climate where gallerists and curators

weren't hanging around like drug dealers at the school gates to capture the

next "new" thing. I would say that the contemporary art world today is much

more like the Paris Salon of the nineteenth century than the world of the

early moderns. But that said, I still enjoy looking at contemporary art in

galleries and museums and fairs. It can be intellectually interesting, amusing

and sometimes very beautiful. It's good to be watchful and alert, but for the

true explorers, it's a good time to look again at the past for some permanence

in a very impermanent world. Also, as I've said many times, making art is a

matter of solving problems and originality doesn't necessarily matter when

you're dealing with more serious issues.

RD: What would you call a serious issue?

DL: A serious issue is creating a culture that believes

in something solid. Let's look at Giotto for example, Giotto recovered a style

of naturalism that better illustrated the stories of the bible but also

created a belief in the beauty of the natural world which led to a greater

desire for truth in the sciences, history and other knowledge-based practices.

The fourteenth century writer, Boccaccio, wrote that Giotto "brought back to

light that art which had for many ages lain buried beneath the blunders of

those who painted rather to delight the eyes of the ignorant than to satisfy

the intelligence of the wise."

RD:

That may have been true for the fourteenth century but I don't buy it for

today. Today it's the ignorant who prefer so-called Realist art and it's the

educated who crowd the Museum of modern Art in New York or the Tate Modern in

London.

DL: Yes, this is true, and huge

numbers of people flocked to the nineteenth century salons in Paris. It's a

more a matter of what is fashionable and popular, being modern or hip is a

great attraction right now, but Realism has played a big part in this

situation.

RD: How so?

DL: Technically speaking, Realism with a capital "R" comes to

us by way of Gustave Courbet. He declared himself a Realist and then made the

point that art should be about the ordinary world immediately around us rather

than the salon paintings of gods and angels, etc. His greatest works, the

Burial at Ornans or the Stone Breakers were about the ironic tension between

the extreme size and care in his depictions of banal subject-matter. His

Realism also created the idea that, in order to be valid, art needed to be

transgressional. I think we owe the whole of the art of the twentieth

centuryto Gustav Courbet.

RD: Do

you really think so? What about abstraction, artists like Mondrian and

Kandinsky or Dadaists like Duchamp?

DL: Yes, well, I believe that they were all realists in their

way. Mondrian wrote a long essay called "Natural Reality and Abstract Reality"

in which he argues that natural appearances veil the deeper underlying

structure. He wanted to create a truth about nature that was greater than the

mere details. He sought the universal rather than the specific. He said that,

"we have to transform natural appearance, precisely in order to see nature

more perfectly." His sense of order suggests to me very orderly things like

time and measure and even gravity. These basic elements are as real as

theleaves on a tree. Mondrian was a profound thinker and his paintings are a

language unto themselves. He was a great artist.

As for Duchamp, by

choosing real objects rather than depictions of objects he ironically one-

upped the Realism of the American Ashcan School of artists like Robert Henri,

Bellows, Glackens and others. He challenged the definition of art itself. He

separated out the idea from the making and also alerted us to the potential

beauty of real life around us. Like Mondrian, Duchamp enters into a Platonic

dialogue that says that the idea is the most important aspect of a work. For

Plato, any imitation removes us from the truth, which for him was the idea of

the actual thing. I personally don't think that Plato's argument against

imitation is about imitation, per se. I think that it's an argument against

the imitation of ordinary reality - the commonplace - exactly the kind of

ordinary reality that Courbet and others were promoting. It's the argument

that you often hear, that art should be a reflection of the times or of 'real'

life - a mirror held up to reality, etc. The truth is, too much looking in the

mirror is not a good thing. Whether by way of Realism or Modernism or any

mixture, too much looking in the mirror is narcissism.

RD: So, if you are, as you say, a classicist and

you believe in Plato then how do you justify your own highly representational

if not Realist work?

DL:

Well, the truth is that I don't believe in everything that Plato (or Socrates)

says. But I think that we're not really meant to believe everything. Plato's

Republic is an exercise in agile thinking. One of the most important lessons

from the ancient Greeks is to be able to hold two opposing opinions at the

same time and then to be able to explore and even defend each if need be. For

instance, believing thoroughly in the redemptive possibilities of idealistic

representation, as I do, while, at the same time, understanding the value of

the most so-called "radical" art of the past two centuries - the centuries

that define who we are.

But coming back to a narrow definition of

Realism, the, shall we say, tender reproducing of the ordinary world around

us. It can be beautiful and revealing to see the mirror held up to reality but

Plato's goal for his ideal city (in The Republic) was to create extraordinary

people and he felt that that was not accomplished by imitating ordinary things

or ordinary people. I can't tell you how often I've read reviews of

exhibitions where the writer says that so-and-so's work is unusual or

refreshing because she or he shows us the world as it is, warts and all,

rather than an idealized world, as if this was something original. It's a huge

cliché!

RD: Yes, but is not the critic

admiring an honesty about the work?

DL:

Honesty can be a very short-term practice. It's better to be involved in a

high fiction than in low honesty - unless, of course, we're talking about

religion.

RD: Let's stay with art,

can we? Isn't there a danger of authoritarianism in Plato's Republic and in

Classicism in general?

DL: Yes there is,

actually, and people have taken it in that direction - the brief but horrible

period of European Fascism for instance. Many, however, confuse the words

authority and authoritarianism. There is a much richer history of Greco-Roman

classicism countering authoritarianism than promoting it, say the European

humanists challenging Christian dogma in the 14th and 15th centuries and the

revolutionaries confronting the crowns in America and France. Think of Thomas

Jefferson's University of Virginia, for instance, or Jacques Louis David's

"Oath of the Horatii" these are neo-classical masterpieces and they draw on

the great foundational languages of ancient Greece and Rome yet they were made

over two millennia after the fact. Those who say that it's not possible to

revisit the past or that it has to be dressed up to look modern are just plain

wrong. The great and influential 16th century French artist, Nicolas Poussin

never once painted a current event or a person dressed in contemporary

clothes. And yet, people drew meaning from his work that, with the use of a

little of their own imagination, could be applied to their own lives. In the

19th century when historicism had been exhausted there was a demand that art

must be about the contemporary – meaning Realism. As they loudly proclaimed,

"one must be of one's own times." That proclamation itself has now become

exhausted. It's time to reconsider history again.

RD: Yes, well, that said, I'm not entirely convinced that

this can be done in this day and age - to revisit the past like Poussin or

David. There are too many obstacles within our own modernness that prevent it.

Too often the sincere artist ends up with pastiche or, worse, kitsch. It's

virtually impossible to suspend belief and seriously accept models dressed in

togas.

DL: I agree, it's very, very

difficult and I can't claim never to have wandered over the border into kitsch

myself. I knew when I began my project that making paintings of people in

historical clothes was very problematic. That was one of the reasons I did it.

It was dangerous, it was totally against the art laws. And thirty years on,

it's still is challenging. How to see outside the gravity of our own time has

occupied me greatly. As I said, Realism in its many forms is part of the

reflection of self. I have very consciously tried to make paintings that are

neither self-expressive nor self-referential (to the extent that that's

possible). What I have tried to do is to make paintings that are abstracted by

time rather than style and that illustrate stories that might have some

contemporary application as well. I'm sure that all recurrent classicists have

done the same. As I have said many times, the Greeks absorbed something from

all of the cultures that they came into contact with, the Egyptians, the

Phoenicians, the Minoans, even the Persians, creating in the process an

enormously inclusive rather than exclusive ideal. Consequently, This "fullness

"or "wholeness" has been able to inform almost every succeeding century.

Whether we like it or not, the model for the very way we think in the western

world, our very psychology, was established by the Greeks 2500 years ago.

RD: There have been many artists in recent

years who have applied classical elements to their work. I'm thinking of, say,

Carlo Maria Mariani, Herman Albert or Nancy Spero. At one point they were

being called Post-Modernists but, of course, now Post-Modernism has a broader

meaning. So, how have you gone about applying Classical ideals to your work?

DL: There have not been so many of those

artists, really. Most of the post-modernists you're talking about were using

classicism or tradition ironically. But when I began thinking about using

Greco/Roman Classicism and narrative I didn't know anyone who was using it.

Since the Second World War it was totally off-limits. I had no idea what I had

gotten myself into when I began. I had zero education in the Classics. I

simply began to read, visit the sites and look in the museums. One of the

earliest realizations for me was that the essence of Classicism is balance-

the balance between opposing forces - Say, Apollonian order and Dionysian

chaos. I learned later that in 1872 Nietzche had written a long essay about

this called, The Birth of Tragedy. In it he describes this duality as the

"primal unity."

That said, I wanted to make paintings that had a wholeness

about them and I discovered that very often whole systems have been described

as thirds. Aristotle wrote that "The whole is tripartite, it contains a

beginning a middle and an end." Plato, in "The Laws," described a work of art

as consisting of mimetic correctness, usefulness and attractiveness. For

myself, I decided that I wanted my paintings to contain the elements of

structure, surface and content. This, of course, created an argument for me

between the number two and the number three. Which was the true essence of

classicism, the balance between two opposing forces or the combination of

three interlocking elements? The answer came for me from an engraving by

Albrecht Durer of a nude woman and a satyr sitting on the ground, a nude man -

probably Hercules - holding his club to fend off a blow to the Dionysian

couple by a robed female. Although it's not known what all of the symbols in

the Durer image represent, it's generally thought that this is his version of

the choice of Hercules between Virtue and Vice.

RD: But that theme as it was presented by Prodicus, as I

recall, was the young Hercules being presented with the choice between an easy

and happy life of pleasure and a difficult but ultimately heroic life.

DL: Yes, and this is what I mean by the

timelessness of recurrent classicism, we all face these choices in our lives.

But I think that the idea of choosing one or the other is false. If the

essence of classicism is balance, we have to embrace both pleasure and virtue.

It's the solution to the argument between the number two and the number three,

the third integer creates the whole and maintains the balance, the "primal

unity."

RD: That sounds like a compromise rather than a

distinction.

DL: Compromise IS a

distinction. It goes along with what I said about being able to hold two

opposing views at the same time. But, but, I'm not really talking here about

art which is either easy or difficult. The most laborious representation can

be, as Goethe put it, nothing in the end but "empty realism" and the most

minimal abstraction, say, can have a profound and spiritual presence about it.

No, there's nothing inherently wrong with any of the modern methods or styles

it's just that they have become totally accepted and expected and academic

within the art establishment.

RD: You said that before. What else can art be,

then, if not what it's been for the past hundred and fifty years and by way of

the various realisms you've described?

DL:

The deeper function of art and culture is to fulfill societal needs. Very

early on its function was probably to honor the animals being hunted by

painting respectful and observant images of them on cave walls. They were not

decorations, they were meant either to give thanks or to please the gods of

the hunt. What we need more than anything else at this period is a renewed

desire for knowledge, "desire" being the operative word. I don't ultimately

have the answer to your question. I have felt that it would be useful to

return to Greco-Roman classicism because the Greeks most particularly were so

intensely curious about every aspect of the world around them. Pericles

described Athens in its golden age as "cultivating refinement without

extravagance and knowledge without softness." We need that kind of inspiration

again. The Egyptians not-with-standing, the Greeks brought into focus the full

depth and complexity of the human mind and hand. They created the origins of

western thought. Theirs' is an entirely different and more profound kind of

originality than simply doing something that no one else has done.

So, to

answer your question, "what else can art be?" I've written before about the

"tragic function" of art. That is, how to see deep into the proud and

vulnerable heart of the world. Realism as it is most often practiced today

subverts that by keeping us attached to the mere appearance of things. Realism

in all its various manifestations has caused us to be fatally fascinated by

our own reflections. I would rather see artists searching for something more

universal and timeless, maybe defining what Eliot called "the presence of the

past." But what is most important is creating an art that inspires our society

to once again wish to imitate not just appearances but excellence itself - the

innate excellence of the human spirit that the Greeks called "arete."

RD: But what would this, let's say, anachronistic

art look like?

DL: Well, I'd like to think

that it would somehow look like what I have been attempting to do for the past

thirty-plus years but that's too self-serving an answer. You're saying

"anachronistic" in a slightly snarky and ironic way. Irony is to Modern art

what sentimentalism was to the salon-art of the 19th Century. Some of the

artists I admire most were anachronistic; Brunelleschi, Poussin, J.L. David,

etc. Escaping the gravity of our own times is going to take a much bigger leap

of imagination than any of the programmatically eccentric or predictably

transgressive art of today has shown. I think that it will be highly

representational because the process, what I call "perceptual analysis"

requires that the artist ask him or herself rational questions about looking

at nature very carefully, analyzing it and then reproducing it

Content-wise,

really radical art needs to reject nearly everything being done today from

purposefully obscure wordworks to "provocative" installations to intentionally

"bad" paintings or videos and also to sweetly naive still lifes, landscapes

and figures. What is needed now is a new ideal promoting the realization that

we can't meet the challenges of the future by being ordinary, ironic or

cynical. I fully believe that every population, no matter what ethnic or

racial makeup has the potential for doing extraordinary things – if they are

so inspired. We have seen that very early peoples made art which was highly

skilled and observant and filled with a sense of the importance of a

correctness (orthotes in Greek). A belief that art could be metaphysical in a

way that it hasn't been recently, meaning that it has the power to transform

life.

So, I would say that the new art would have to counter and to

contradict almost every aspect of what we now call "contemporary art." It

should find a new way to engage with history and to have, as Eliot said a

"simultaneous order." It needs to enlarge us by way of our sense of our place

in time and to prepare us for the challenges of the future. More than

anything, our art and our culture needs to create the renewed desire for

knowledge. This is the new challenge, the new ideal and the new modernity.

Florence, Italy 2011

Download a pdf of this essay

Download a pdf of this essay

Claude Lorraine: The Painter as Draftsman by David Ligare

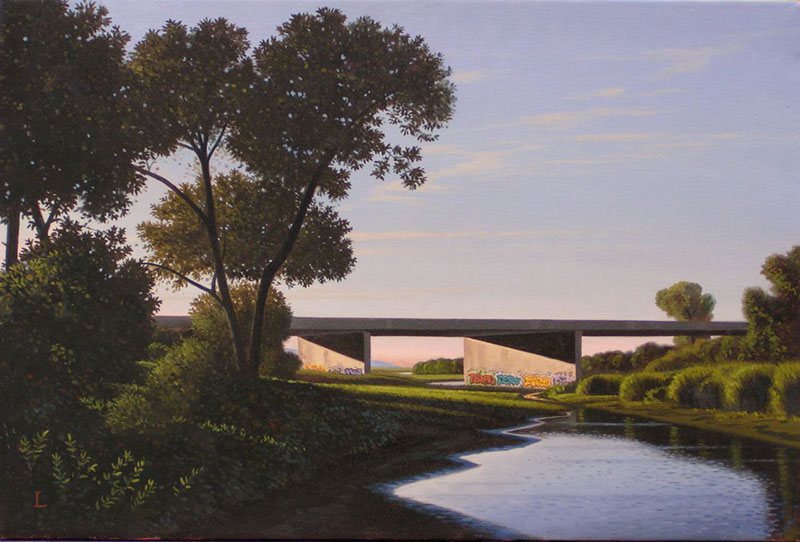

Claudian Landscape with Graffiti, 2009

It's not often that we have the chance to experience something that is the best that the world has to offer. During the last hectic days of the year I strongly recommend that everyone within range of these words make a pilgrimage to the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco to see the exhibition, Claude Lorraine: The Painter as Draftsman. There are approximately eighty drawings, mostly from the British Museum, and a dozen paintings. The drawings are quite simply the most beautiful drawings of the landscape in all of the long history of art. The exhibition closes January 14th.

Briefly, Claude Lorraine (generally called Claude) was born in France in 1600 but lived his entire adult life in Rome. Despite achieving great fame while he was alive, very little is known about his personal life. It seems that he was a simple and uneducated man who, nevertheless managed to inform his world and ours in major ways.

What was Claude's conceptual project? According to his fellow painter, Sandrart, he would lie out in the fields from dawn to dusk storing up the visual effects of light in his brain. In that way he was like the Impressionists who worked two hundred years later. But unlike, say, Monet, whose impressions shattered the world into shimmering bits of color, Claude sought to present a cohesive naturalism. In other words, all of the chaotic elements of nature fell into a sense of poetic order and wholeness. His paintings invariably contained a detailed foreground (often flanked by embracing trees), a middle ground of winding rivers or roads leading to an exquisite distance paled by sunlight and atmosphere. They are like Aristotle's definition of life; a beginning, a middle and an end. Claude's paintings continued the "pastoral landscape" tradition started by the Venetian artist, Giorgione (1478 - 1510). Claude's project was to present images of a wholeness that heightens our perception of a radiant world.

The process for making his large detailed landscapes was complex. Plein air painting was very difficult because portable oil colors in tubes had not yet been invented. In addition to mental observations, Claude would make ink and chalk studies on paper. These studies could be detailed, or they could be very rapid and free, having all the vigor and angular dash of the twentieth century Abstract Expressionists. Most of the drawings are in brown sepia ink which can add a hovering or seeping glow that might be compared to the deep spiritual hum of the paintings of Mark Rothko. He would return to the studio with these notations and impressions and use them to construct his large and carefully detailed compositions.

But Claude's drawings are also fundamentally different from the intentions of the Impressionists or the Abstract Expressionists who were primarily interested in line, shape and color for their own sake. These drawings, which often employed quickly dashed lines, dragged brushes and blossoming washes are not meant to be interesting in and of themselves. They were short-hand notes to himself analyzing and describing what it was he was seeing. As a result they have a simple honesty filled with an almost religious belief in the beauty of nature. The process of trying to capture and understand the integrity of that nature is well-tempered (as in Bach) by a structured tone of richness and order.

The viewer will see two types of drawings in this exhibition. The first are the studies that I have described, the second were drawn from the finished paintings as records, his Liber Veritatis or verification book. These drawings have a different, less searching, look to them. Still the pen and the brush dance across the surface of the paper but they have an almost painfully naive completeness about them.

Claude Lorraine worked over three hundred years ago. It's wonderful to see his paintings and drawings in the Legion of Honor but how could he possibly relate to us today? After viewing the exhibition I suggest going immediately to Golden Gate Park and, say, walking around Stowe Lake. If you are like me, the landscape there will be transformed after viewing the drawings and paintings. This is not just coincidental. Claude had a huge influence on landscape architecture in eighteenth century England. Many of the manor houses were surrounded by parks designed to look like Claude paintings. This style was called "the picturesque landscape" and one of its later proponents was the Scottish-born landscape architect, John McLaren who, along with William Hall, created Golden Gate Park from the stark, windswept dunes.

Visiting Golden Gate Park or viewing the paintings and drawings of Claude Lorrain presents us with a median world: a buffer zone between urban life and wilderness. They are also timeless, often with people living among ruins. Thus the paintings and drawings are essays on mortality - the passing of a civilization or the closing of a day. He returns us to the poetic world of the pastoral tradition. That tradition and Claude put us in mind of the beauty and fragility of our own mortality, the joy of attainment and the dearness of our natural world.

Published in the Monterey County Weekly, December, 2006

Download a pdf of this essay

Download a pdf of this essay

The Big Sur: Paintings by David Ligare

Big Sur Landscape: Grimes Point, 2012 o/c, 40 x 60 in. Winfield Gallery, Carmel, CA

Inspired by the writings of John Steinbeck and Robinson Jeffers I moved to Monterey County while in my early twenties. I was fortunate to find a small house on Rancho Santa Margarita in the Big Sur where I was surrounded by the wild beauty that Jeffers had described so profoundly. At the same time I was exhibiting my paintings in New York (a contrast I relished) and I was experimenting, as young artists do, with new styles and concepts.

Now, more than forty years later, I am again looking at the landscape of Big Sur. Many styles and fashions in art have bloomed and faded in that time but the landscape of the south coast has remained virtually unchanged. There is an immense power and dignity about Big Sur with its broad, golden shoulders set against the cool sweep of the sea. I believe in the value of recognizing the integrity of the thing seen, that is, in representing every element of nature as carefully and reverently as I can. In certain respects this attention to detail and place is reminiscent of the New Path artists of the mid-nineteenth century or the f64 photographers like Weston, Adams, Cunningham and others. They all turned away from the artful and the "painterly" to embrace the literal. In both cases the artists/photographers in question approached their subjects with an insistent honesty and deep fidelity to nature.

Finally, there is the light. To see and to present the Big Sur in the intense golden light of the late afternoon is to celebrate the great beauty that burns there. Every hill, copse of trees, ragged stone or spread of sea is bathed, molded and carved by the light. Time stands still and it is that exact timelessness - without the qualifier of human activity or artistic style - that interests me.

David Ligare, 2010

Download a pdf of this essay

Download a pdf of this essay

Aparchai: Ritual Offerings

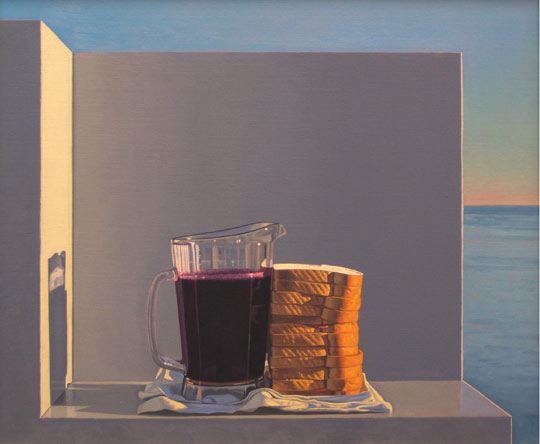

Still Life with Grape Juice and Sandwiches, (Xenia),1989 o/c, 20 x 24 in. Collection: DeYoung Museum, San Francisco, CA

In 1989 I painted a still life of a pitcher of grape juice and a stack of sandwiches, now in the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco. The pitcher and the shape of the sliced loaf of bread were distinctly contemporary but the sub-title of the painting, "Xenia," put the objects into the realm of history painting.

In ancient Greece, according to the Roman writer Vitruvius, when one had houseguests, "on the first day they would be invited to dine with the family, on the next, chickens, eggs, vegetables, fruits, and other country produce were given to them to eat in their own quarters. This is why artists called pictures representing the things that were given to guests "xenia." In my case, the bread and sandwiches depicted were exactly those served to homeless people in a soup kitchen where I volunteered in Salinas, California. They were literally, xenia or food gifts for strangers.

Another genre of still life painting in ancient times was the depiction of ordinary objects that played paradoxically with the extreme care with which they were created. These were called rhopography, The best example of these was a floor mosaic from Pergamum called "The Unswept Floor," with the remnants of a meal scattered about. There are bits of bone, husks from nuts, a seashell, a bird's foot and even a very real-looking mouse nibbling on a nut.

It has been thought by historians that most existing images of foodstuffs painted in ancient times are either xenia or rhopography, indeed any real evidence to the contrary is nearly as lost as Greek still life paintings themselves. But I believe that there is another category of imagery - hidden in plain sight - that has not yet been recognized by scholars.

About ten years ago, I began looking and thinking more carefully about the paintings found in ancient Roman Pompeii and Herculaneum. Many of the images were clearly not of items that one would give to a houseguest to eat. The most famous example, usually described as a xenia, is of four peaches and a glass vase of water from Herculaneum. It's a very beautiful painting but as a xenia it represents a scant meal - with green, seemingly inedible peaches. I recalled from travels in Nepal seeing small shrines with offerings of fruit, rice or flowers and I wondered if these peaches might have served a similar function. I confess that, while I had made a careful study of Greek art, I had spent no time studying Greek religious practices. Art history texts generally ignore religious practices and the surviving ancient writings may neglect them because they were so commonplace and deeply ingrained. The casualness with which these rituals are performed in Nepal attests to both the obvious depth of belief and the off-handedness of their practices. Ritual offerings seem simply to have been taken for granted as a part of everyday life.

In ancient Greece, ritual offerings and sacrifices may have been extremely commonplace but, according to Historian Walter Burkert, "The most important evidence for Greek religion remains the literary evidence, especially as the Greeks founded such an eminently literary culture. Nevertheless, religious texts in the narrow sense of sacred texts are scarcely to be found." I would add that evidence depicted on Greek vases is suggestive, if not necessarily specific, of religious practices. Presumably easel paintings (pinax) of which there were vast numbers, would also have included depictions of processions, offerings, sacrifices, burials and other rituals.

Still Life with Olives and Wheat,(Aparchai), 2012 o/c, 20 x 24 in. Hirschl & Adler Modern, New York

The ritual of first-fruit offerings was deeply ingrained. Burkert writes that "an elementary form of gift offering, so omnipresent that it plays a decisive role in…the origin of the concept of the divine is the primitial or first fruit offering, the surrender of firstlings of food whether won by hunting, fishing, gathering, or agriculture. The Greeks speak of ap-archi, beginnings taken from the whole, for the god comes first." But without specific textual proof that early still life paintings represented aparchai, how do we know that it might be so?

First, there are the surviving wall paintings from Pompeii and Herculaneum that depict imagery of foodstuffs in conjunction with small votive statues of Dionysus or Demeter, goddess of the harvest. In these original pine panel paintings (later recreated in fresco, including their frames) the depictions might be stand-ins for the offerings themselves, or representations accompanying the offerings or perhaps allegorical images expressing piety. William Rouse in his book, Greek Votive Offerings, notes that, "the offering in kind was often commemorated by a model." He cites gold sheaves of wheat left at the temple at Delphi, gold clusters of grapes at Delos and even a golden radish. In the National Museum in Reggio Calabria there are many terracotta models of fruits and vegetables found at the Temple of Demeter. Animals were also depicted: a gold deer dedicated to Apollo, etc. Indeed, all manner of enterprises might be represented in kind. Herodotus wrote that "Mandrocles, who built Darius' bridge over the Bosphorous, spent part of his fee on a picture of the bridge which he dedicated to Hera in Samos for a firstfruit."

And so it seems clear to me, with these and other evidences, that it is entirely possible that many early still life paintings were representations, not just of hospitality gifts (xenia), or pleasurable arrangements of ordinary objects (rhopography), but, that they may have been intended to metaphysically stand in for or accompany offerings of thanks to the gods (aparchai). Within the art history community, a new archeology is needed to look more carefully at this wholly overlooked genre of ancient art.

David Ligare, 2012

Works Cited:

Burkert, Walter. "Greek Religion." Harvard University Press, 1985, pp. 66-67 Rouse, William Henry Denham. "Greek Votive Offerings: An Essay in the History

of Greek Religion." Cambridge:At the University Press, 1902, pp. 39 - 93

Vitruvius. "The Ten Books on Architecture." Dover Publications, 1960, p. 187

Download a pdf of this essay

Download a pdf of this essay

On Originalities

When I began my project to make historical narrative paintings more than thirty years ago I had accepted that there was a tremendous diversity in contemporary art making and that virtually anything could now be considered as art. I decided that I would simply set aside that book without complaint and do something completely different - something that no one - or almost no one - else was doing, that is, make narrative paintings based on Greco/Roman culture. I had for a guide the New York Artist and critic, Sidney Tillim who had written an article entitled, Notes on Narrative and History Painting. In this brave and utterly original essay in Artforum Magazine, the most avant garde publication, he wrote that, "…history painting is nothing more or less than a dogmatic approach to the problem of originality. It consciously attempts to graft onto the hide of history a contrary notion about art and culture… By originality, then, I mean nothing like a 'breakthrough' in the modernist sense, but a feeling for the figurative tradition so strong that it seems radical." At a time when radicalism was and has been conventionalized by the comfortable embrace of museums, critics, collectors and galleries, making what I came to call "the literate picture" seemed daring to me - not just daring but necessary as a counter-balance to the predictability of almost all contemporary art and because we were and are in need of a renewed knowledge-based culture.

Tillim's writing as well as his paintings gave me license to think in ways that were totally out of fashion and thus wonderfully fresh and dangerously outside. My decision to dress my figures in classical, or quasi-classical clothes went against the Renaissance tradition of updating ancient dress in paintings to fashions of the present day. But updating in that way would make me a realist and I felt that we already had enough realists holding up the mirror to contemporary life as part of our total obsession with nowness.

What I wanted more than anything was to search for the center or the source of western art. I sought to understand the underlying principles of Greek culture and found that those included fundamental concepts that have returned in many forms over the intervening centuries. For instance, one of the most essential aspects of ancient Greek art was the duality between order as represented by Apollo and chaos represented by Dionysus. Neitzsche, in his 1872 essay, The Birth of Tragedy, describes this duality as a "primal unity." He writes that, "Here we have presented, in the most sublime artistic symbolism, that Apollonian world of beauty and its substratum, the terrible wisdom of (Dionystic) Silenus; and intuitively we comprehend their necessary interdependence." My painting, Hercules Protecting the Balance between Pleasure and Virtue is one of many paintings where I refer to that "primal unity."

In this period of intense popular distractions, a strong disinterest in education and what the art historian, Hugh Honour has called "the fashion-conscious mania for novelty," I want to attempt to make paintings that return to origins - another kind of originality. Therefore, I believe in painting that attempts to convey specific meaning by way of the abstraction of history. I also believe that representation (perceptual analysis) is important because it has the potential to make us see more clearly and rationally. But as Sidney Tillim wrote, "Belief, like good intentions, hardly guarantees anything, originality least of all, but the manner of its occurrence, like originality, cannot be anticipated. So that, if representation per se is not new or 'surprising,' its conviction in contemporary terms can be."

David Ligare, 2010

See Sidney Tillim, Notes on Narrative and History Painting, Artforum, May, 1977, p. 41

Download a pdf of this essay

Download a pdf of this essay

The return to the classical past is conceived as a return to origins. However, as each generation, through repetition, creates its own fixed norms, so that what was once new comes to represent the oppressive Establishment, the succeeding generation becomes dissatisfied, demanding a renewal and a return to yet more 'original' forms." Elizabeth Cowling, On Classic Ground: Picasso, Leger, DeChirico, and the new Classicism 1910-1930 Tate Gallery, London, 1990

"Nietzsche argued that the 'serenity' claimed by (classical historian) Winkleman to be at the very heart of Greek art, and which Nietzsche termed the 'Apollonian' ideal, was, in reality, a sublimation, a necessary antidote to the forces of terror and anarchy," Elizabeth Cowling, On Classic Ground, 1990

Interestingly, Ligare does not reject conceptual art, he absorbs it recognizing the primacy of “idea” while also acknowledging the importance of what he calls “visual literacy.”

“One of the most important functions of art now is to make sense of the world through careful and rational analysis and the perspective of history.”

David Ligare, Paintings

Catalog Introduction, 1997

This catalog is not so much a presentation as a proposition. It follows the exhibition of a selection of my paintings titled “Landscape & Language” at the Monterey Museum of Art in Monterey, California. That exhibition, like all my work for the past twenty years, sought to reconnect the viewer with what the artist and critic Sidney Tillim called “purposeful representation.”

In the exhibition and in this catalog, I am proposing an art that seeks to communicate specific ideas that knit us together through common historical knowledge. For me, it seemed especially appropriate to make this proposition in connection with the Monterey Museum, an institution that specializes in the unique history and profound beauty of this region.

In 1978, when I set my present course of trying to understand and to use the visual language of Greco-Roman history in my paintings, I consciously looked for stars by which to navigate. The two stars I chose among so many were Polykleitos, the fifth-century BC Greek sculptor from Argos, and Nicolas Poussin, the French artist who painted in Rome during the seventeenth century. The work of both of these artists represents images and ideas that have contributed greatly to what I call “recurrent classicism.”

Polykleitos’ most famous statue, the Doryphoros or Spearbearer, was a bronze figure that embodied the sculptor’s canon—a treatise on ideal proportion. More than that, however, it outlined the concept of symmetria, which did not mean balance as much as it meant the integration of the varied parts of the body by a system of mathematical proportions. Symmetria literally means “the commensurability of parts.” Polykleitos helped form one of the foundations of Western thought: that there is a substratum of harmonic relationships that underlies all nature and human social interaction. In other words, it isn’t just the individual members that are important, but the interrelationships between them.

Twenty centuries later, the painter Nicolas Poussin embraced much the same philosophy. The underlying structure in his paintings at times utilized the harmonic proportions of the Greek modes, or ancient musical arrangements. The hidden geometry of the picture became a visual equivalent of music that provided, according to Poussin, “a subtle distinction, particularly when all the things that pertained to the composition were put together in proportions that had the power to arouse the soul of the spectator to diverse emotions.”

This same proportional structure aligned and organized all of the lovingly realized elements depicted in Poussin’s paintings. Each figure, tree, and cloud had an integral relationship to the whole of the composition. Moreover, Poussin used these elements to tell stories that offered to the viewer moral and intellectual lessons. He often selected themes that suggested an individual’s potential for virtuous action.

When I began analyzing paintings like those of Poussin, I concluded that there was a fullness about them that could be broken down into three basic elements: structure, surface, and content. The structure included the geometric design and proportions, the surface was the look of nature reverently recreated with brush and paint, and the content was the theme or story whose purpose was to communicate a specific idea to the viewer. This tripartite criterion for a work of art has guided me ever since.

The richly beautiful landscapes of Monterey County, where I have lived for much of my life, provide the setting for most of my paintings. Because California actually looks so much like Italy, Greece, and Spain, and because its earliest European immigrants were from the Mediterranean, it seems fitting to substitute one for the other. Finding or inventing an ideal landscape and filling it with narratives or stories of human endeavor is once again new territory for the artist.

There has been widespread mistrust of classicism in the late twentieth century. It is believed by many to represent authoritarian or elitist ideas. In fact, the opposite is true. Art historian Andrew Stewart writes that the Spearbearer was viewed in its own time as “an ‘everyman’ free of individual peculiarities and quirks.” As I have said, it is an essay on physical and social integration—the diverse many coalesced into one. As the scholar Robert Proctor has written, “We can recognize that the ancient problem of the one and the many has come back to haunt us, and we can study the particular solutions to this problem worked out in antiquity.” It is extremely important to note that the canon of Polykleitos exactly coincided with the age of Pericles and the flowering of the world’s first democracy.

It is my strong belief that the classicism of ancient Greece possesses a fundamental relevance. That is why, despite its many “deaths” over the centuries, it has always returned. As I wrote for the University of Notre Dame in 1991, “Classicism was an amalgam of styles and ideas from the earliest and smokiest of times. It absorbed something from all of the cultures that it came into contact with, from Egypt and Africa to Asia, creating in the process an enormously inclusive rather than exclusive ideal.”

Polykleitos, Poussin, and many others provide us with a much-needed model for a new ideal. The new ideal that I propose is based on the classical model that is best represented by the Doryphoros. It includes the integration of diversity, virtuous community participation, reverence for nature, the radical pursuit of knowledge, and the embracing of the full implications of humanist beauty.

David Ligare